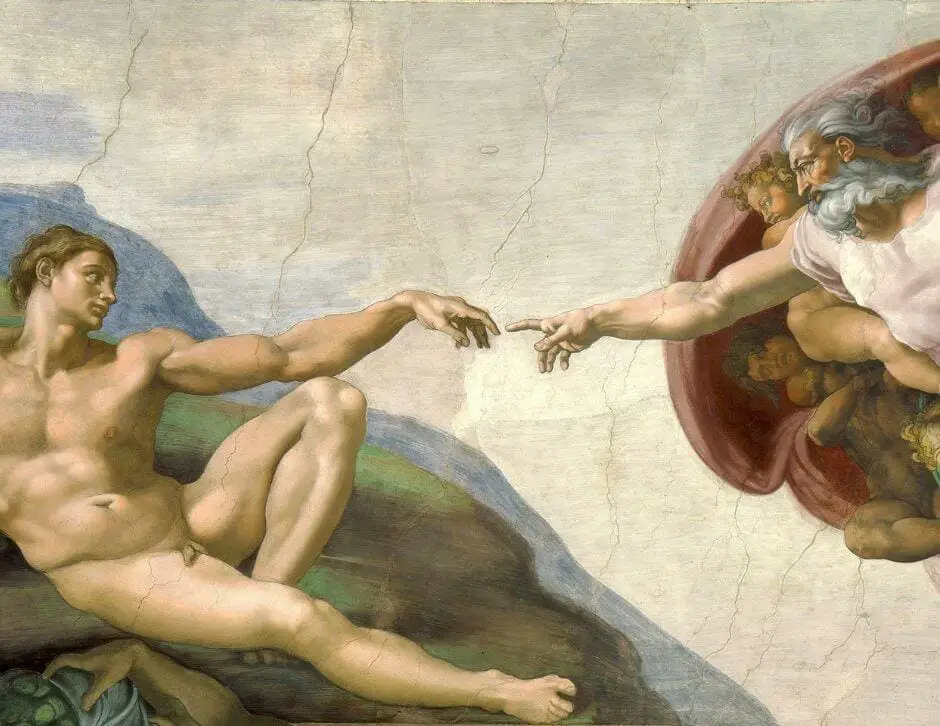

Michelangelo’s ‘The Creation of Adam’ is not merely a visual triumph but a narrative embodied in paint, a complex conversation between art and viewer that has captivated audiences for centuries. Situated on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, this fresco intertwines divine narrative with the human condition, a synthesis of faith and finesse that epitomizes the brilliance of the Italian Renaissance.

As we unpack the layers of iconography and symbolism, we behold an image dense with meaning—where the almost-touching hands of God and Adam suggest an intense moment of potentiality. In this space between divine intent and human reception, we explore the meticulous artistic techniques, the resonant historical context, and the multilayered legacy left in the wake of Michelangelo’s brush.

Table of Contents

- Iconography and Symbolism

- Artistic Technique and Composition

- Historical and Cultural Context

- Impact and Legacy

- Related Questions

Iconography and Symbolism

Unveiling the Symbolism within the Creation of Adam by Michelangelo

When beholding the magnificence of Michelangelo’s ‘Creation of Adam,’ one is immediately enraptured by the luminescence of humanism juxtaposed with the divine.

Crafted amidst the peak of the Renaissance, the fresco that graces the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel stands as a testament to not only Michelangelo’s unmatched skill but also to the deep undercurrent of symbolism that breathes life into its figures.

At the heart of the fresco is the profound moment of the divine spark—God imparting life into the first man, Adam. Yet, the subtle intricacies and layered meanings behind the elements adorn this masterpiece, which beckons closer examination.

The figures of God and Adam are the focal points, their near-touching hands becoming an iconic symbol worldwide. God is depicted within a nebulous, brain-like shape, hinting at a possible allegory: the birth of intellectual enlightenment and the divine inspiration that fuels human creativity.

This visual representation serves a religious function and symbolizes the Renaissance’s awakening, a period marked by a reinvigoration of arts, science, and philosophy.

Adam’s posture and incomplete connection with God underscore man’s eternal struggle with human limitation and frailty. His relaxed pose, with one arm stretched towards the Almighty while the other lies idle, reflects a spiritual lethargy, suggesting humanity’s reliance on divine intervention to fulfill potential.

The figures surrounding God have intrigued scholars for centuries. The most prominent, a female figure under God’s left arm, is traditionally identified as Eve. Yet, some propose she may also represent Sophia, the personification of wisdom, indicating that knowledge is as much a creation of the divine as man himself.

The various interpretations herald Michelangelo’s intricate dance with theology and intellectual discourse.

The separation between the celestial and earthly realms using contrasting spaces—God enveloped in a dynamic swath of drapery amidst a multitude of angels and Adam situated on a barren landscape—intensifies the threshold between the divine and mundane.

Such a portrayal reinforces the Renaissance belief in the potential of human beings to achieve a higher state of consciousness through the guidance of a higher power.

Even the selection of colors speaks volumes. Michelangelo opts for subdued hues for Adam and more radiant tones for the Almighty, suggesting a hierarchy of vitality and a gradient of existence from the heavens to the earth.

In summary, every element of Michelangelo’s ‘Creation of Adam’ pulsates with symbolic implications. From the anticipation-charged space between the fingertips of God and Adam to the enigmatic figures shrouded in celestial mystery, Michelangelo invites an enduring dialogue between the earthly and the divine, encapsulating the essence of Renaissance humanism.

As onlookers, we are offered a glimpse into an eternal narrative that insists on being observed, deeply contemplated, and eternally revered.

Artistic Technique and Composition

Unveiling Mastery: Michelangelo’s Pictorial Choreography in ‘The Creation of Adam

When one gazes upon the Sistine Chapel’s grand vault, “The Creation of Adam” by Michelangelo commands attention not simply as a majestic narrative piece but as a testament to the artist’s unparalleled ability to imbue painting with life, creating a sublime aesthetic experience.

Michelangelo’s technique is the silent articulation of emotion and ideology, expertly crafted to amplify the fresco’s profound impact on the observer.

The meticulous choreography of Michelangelo’s brushwork orchestrates a form of visual poetry. Through sfumato—a technique characterized by the delicate blending of colors—Michelangelo achieves an ethereal realism, making the figures appear to emerge from the plaster and breathe within the chapel’s air.

Notice how the shadows and light dance on the figures, bestowing them with dimension and weight yet retaining an otherworldly grace.

This celestial drama is heightened by the artist’s profound understanding of anatomy. Michelangelo’s previous anatomical studies pay dividends in the muscular tension and relaxation visible within Adam’s physique.

Every sinew and muscle on display is a silent yet powerful discourse on the human condition, both in its potential and current state. The skin’s tactile quality and the flesh’s fabric-like fold affirm the artist’s dedication to representing the human form not as a mere vessel but as a temple worthy of the divine spark it is about to receive.

Driven by the dynamic interplay between potent gestures and impassive stances, the narrative unfolds with an almost musical rhythm. The anticipation in the space between God’s active outreach and Adam’s passive demeanor creates a visual tension—a dramatic pause—that encapsulates the very essence of the moment of creation.

This compositional choice is perhaps one of the most striking elements of Michelangelo’s technique, as it involves the viewer in the unique temporality, the ‘before’ that anticipates the ‘after.’

Moreover, the artist’s use of chiaroscuro brings about a striking contrast between the radiant illumination of the divine assembly and the comparatively muted tones enveloping Adam.

This approach not only accentuates the spatial and existential divide but also lends a voluminous quality to God and his entourage, reinforcing the omnipotence of the Creator contrasted with the vulnerable incompleteness of the first man.

Further enriching the visual impact is the intricate architectural setting—God enshrined in an anatomically suggestive shroud—mirroring the human brain. Michelangelo bridges theology and science, inviting contemplation of the Creator as the source of life and the genius behind human intellect. The synchrony of faith and reason is brilliantly encapsulated, affirming the Renaissance ideal that art, like humanity, can embody the vastness of divine wisdom.

In “The Creation of Adam,” Michelangelo’s technique is a masterful interweaving of artistry and intellect. Each brushstroke carries a declaration of the divine, every hue and contour a verse in a more extensive dialogue about human potential.

As admirers of this monumental work, we witness not just an act of ultimate creation but the very elevation of the painter’s craft to a conduit for the sacred. It is where theology, art, and philosophy mold into one—a piece to be seen or analyzed and profoundly felt, assuring its timeless impact.

Historical and Cultural Context

Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam,” frescoed on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, is a testament to the artist’s mastery over the sfumato technique. This method allows for the delicate blending of colors to create the illusion of depth, volume, and form.

Integral to the work’s profundity, sfumato envelops the divine scene in a soft haze, beckoning viewers to focus on the central narrative forged by God’s outstretched hand.

In this iconic tableau, the use of shadow and light is not merely functional but deeply narrative. The contours of Adam’s muscular physique gain tangibility through rich chiaroscuro, the stark contrast of light and shade that sculpts the human form.

This depth of understanding of human anatomy is no coincidence; Michelangelo was known to dissect cadavers to gain intimate knowledge of the body—a practice that breathed verisimilitude into the creation of Adam’s sinew and skin.

Indeed, “The Creation of Adam” is packed with the tactile quality of flesh-made paint. Michelangelo captures the complex textures of the human form, rendering Adam with a corporeal heft and a palpable presence.

This sensual modality suggests that Adam is moments from receiving the divine breath—a testament to the painter’s artistry in making inert pigment and plaster embody life potential.

The energetically charged gestures and stances further reinforce narrative dynamism. There is an anticipation in Adam’s languid pose—he is alive but not yet animated.

In contrast, God moves with purpose and direction, carried by cherubic figures that exude celestial motion. These gestures form an arc of storyline that semaphores the exchange of life and intellect—the crux of the creation.

One cannot overlook the intentionally dramatic use of chiaroscuro that Michelangelo applies for visual impact and as a symbolic device. The contrasts of light and dark punctuate the themes of enlightenment and ignorance, presence and absence, knowledge and naiveté. The subtlety of shifting illumination across the composition mirrors the journey from nothingness into being—a cosmic theater penned in painterly expression.

As for the architectural setting that unfolds above the altar, it is far from a mere backdrop. Echoing the grandeur and complexity of the cosmos, it serves as a visual anchor for the theological narrative.

The elaborate scaffolding of sibyls, prophets, and ignudi (nude figures) enrich the painting with layers of symbolic meaning. This symbolic environment becomes a bridge where art and theology convene in dialogue.

In this fresco, theology, and science are not adversaries but co-conspirators in the search for truth. The anatomical precision in Adam’s figure parallels the Renaissance’s embrace of empirical study—a time when artists and scientists were often the same. This synergy of disciplines is echoed in the grand design of the fresco.

Michelangelo demonstrates an interweaving of artistry and intellect, not simply through the depiction of the divine and human figures but also through his approach to painting itself. The application of color, the understanding of light and perspective, and the encompassing atmosphere are all calculated to engage the viewer’s senses and intellect. The fresco is thus a sophisticated orchestration of knowledge and skill, beauty and truth.

Ultimately, the timeless impact and profound emotional experience of “The Creation of Adam” lie in its ability to transcend the medium. The fresco is not merely viewed; it is encountered.

Across centuries, it echoes the vivifying touch of the divine, the awakening of consciousness, and the boundless potential of the human disposition. This celebrated artwork remains a profound emblem of Renaissance achievement, reminding humanity of its inextricable blend of dust and divinity and its endless journey from creation to intellectual and spiritual enlightenment.

Impact and Legacy

The Creation of Adam: A Beacon in the Pantheon of Artistic Genius

In the hallowed halls where art and divinity converge, Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” is a testament to humanity’s pursuit of expressive perfection. Detached from the literal confines of biblical narration, the fresco has sculpted its indisputable place in the history of art, serving as an archetype for myriad cultural expressions that followed.

One cannot overlook the exceptional mastery with which chiaroscuro is employed to provide a sense of volume to the figures and underline the gravity of the transcendent contact. The contrasts, where divine luminescence meets the subtle shadow of mortal flesh, accentuate the narrative’s potency and imbue the work with a celestial gravitas.

The Renaissance era marveled at the symbiotic relationship between art and anatomy, and in no place is this more evident than in Adam’s sculptural form, powerfully influenced by Michelangelo’s intimate knowledge of the human body.

His understanding translates into the convincing volume of sinew and skin, an anatomy lesson draped in paint, revealing the artist’s dual role as creator and scholar.

Embodied within the tactile quality of the figures is a palpable humanism—an invitation to experience the artwork through senses beyond sight. This almost tangible essence challenges spectators to feel the tension in the air, the implied texture of skin, and the sublime stirring of spiritual awakening.

The subtle exchange of gestures between the divine and the mortal encapsulates a narrative far beyond the confluence of two worlds—it weaves the story of human reality. Each pose, from the languid repose of Adam to the purpose-filled direction of God, encapsulates the theatre of existence wherein every gesture speaks volumes of the divine script.

Amidst these human and spiritual exchanges lies the keen interplay of light and shadow through the sfumato technique. This delicate gradation recognizes the invisible transition between the corporeal and the ethereal, reviving the forms with depth and realism and allowing artistry to blossom where celestial and terrestrial narratives meet.

The fresco’s architectural elements act as scenery and symbolic entities, bridging the gap between terrestrial achievements and divine ordinances. The implied spaces and structures suggest an order to the expansive ideas manifesting on the chapel ceiling, anchoring the expanse of celestial narrative into a comprehensible human framework.

Additionally, “The Creation of Adam” paints—quite literally—the dialogue between theology and the burgeoning fields of science during the Renaissance. The painting responds to humankind’s emerging understanding of the world and cosmos while reverently nodding to the sacred scriptures, marrying the secular quest for knowledge with sacred knowledge in a visual symphony.

This profound marriage of intellect and artistic brilliance fuels the everlasting impact of the work. Viewers don’t just observe—they engage with a spectrum of ideas and emotions spanning centuries. A mere brushstroke becomes a conduit of existential reflection, a silent orator of the human condition.

In conclusion, “The Creation of Adam” reverberates through the currents of time as a symbolic piece of Renaissance art and a mirror reflecting the vestiges of human thought, spirituality, and intellectual evolution. It invites countless generations to pause and partake in the shared heritage of human wonderment.

“The Creation of Adam” conserves its magnetic pull on the soul of culture, beckoning the artistic pilgrim to a silent conversation with the past, continuing to resonate with the timeless quest for wisdom, beauty, and transcendence.

The sublime fresco ‘The Creation of Adam’ continues to whisper its secrets to those who endeavor to listen, eluding complete comprehension while ceaselessly inspiring awe. Its allure lies in the enduring enigma—a testament to Michelangelo’s mastery and the Sistine Chapel’s sanctity.

We deepen our appreciation for this monumental work by examining its intricate layers, from its deft composition to its multifaceted aftermath. The preservation efforts that safeguard this fresco ensure that future generations may also look upon it and feel the profound connection across time—a touch from the past that remains vitally present, reverberating with the echoes of inspiration that first danced in the mind of Michelangelo and continue to resonate in the vaults of artistry and imagination.

Anita Louise Art is dedicated to art education, great artists, and inspiring others to find and create their art. We love art that uplifts and inspires. #ArtToMakeYouSmile! #ArtToMakeYouHappy!

If you are interested to see any of my art, you can find out more by clicking here. If you are interested in what inspires me and my paintings, you can discover more by clicking here.

We have a free newsletter and would love you to be part of our community; you can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here. If you have any questions, I would be happy to talk to you at any time. You can reach me, Anita, by clicking here.

Subscribe to our Anita Louise Art YouTube Channel filled with great videos and information by clicking here.

Join us for our podcast “5 Minutes With Art.” Spend just 5 minutes a week with us to discover and learn about great art and artists. You can find out more about our podcast by clicking here.

Related Questions

Guide To The Last Supper Picture By Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper painting is located in Milan, Italy. Even though the painting was so badly damaged, it has been restored and is still considered one of the greatest Renaissance masterpieces ever created. The Last Supper depicts the emotions of the apostles as Christ told them that one of them was going to betray them. The painting is filled with symbolism and emotion.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Guide To The Last Supper Picture By Leonardo da Vinci.

Discovering Van Gogh: Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is a world-renowned cultural institution that attracts art lovers and enthusiasts from around the globe. It is home to the most extensive collection of works by the legendary Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh. Visitors can explore Van Gogh’s fascinating life and career through a diverse collection of over 200 paintings, 500 drawings, and 700 letters. The museum constantly has new and exciting collections that also reflect upon the work and life of Vincent Van Gogh.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Discovering Van Gogh: Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam.

Ukiyo-e Vs. E-Ukiyo: An Important Part Of Art & Art History

Two forms of Japanese art continue to influence Western artists: the Ukiyo-e art and E-Ukiyo. Both of these are unique Japanese art forms. The Ukiyo-e is the art form that emerged in the 17th century. The E-Ukiyo is a more modern art form associated with digital art.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Ukiyo-e Vs. E-Ukiyo: An Important Part Of Art & Art History.