The Baroque period, an era of transformation in European art, reflects the complex socio-political tapestry of the 17th and 18th centuries. As the Counter-Reformation and the establishment of absolute monarchies shaped society’s structures, the world of art simultaneously underwent a dramatic evolution.

The emergence of Baroque art, characterized by its grandiosity, drama, and movement, reflected the times. Not solely an artistic choice, these features were deeply entwined with the artists’ patrons—the Catholic Church and nobility heavily dictating the style’s trajectory movements.

Table of Contents

- Historical Context of Baroque Art

- Essential Formal Qualities of Baroque Art

- Baroque Artists and Their Masterpieces

- Baroque Art: Variations Across Europe

- Influence and Legacy of Baroque Art

- Related Questions

Historical Context of Baroque Art

The Baroque Canvas: Historical Contours Shaping an Artistic Revolution

Envision the 17th century: a turbulent era of sweeping changes and dramatic contrasts. This period gave birth to a style of art as dynamic and opulent as the historical forces from which it sprang. This was the age of the Baroque, a term derived from the Portuguese ‘barroco,’ initially referring to a rough or imperfect pearl.

Yet, far from imperfect, Baroque art emerged as a robust pearl in the history of visual expression, shaped and lustrously polished by the clamor and zeal of its era.

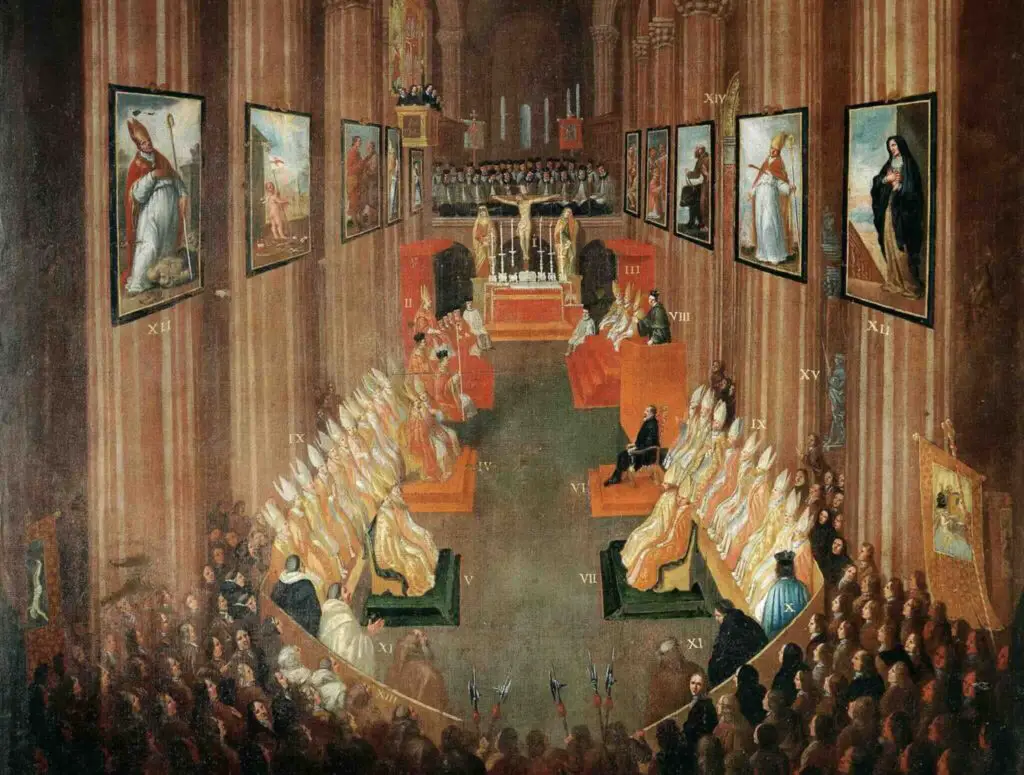

The Baroque period, roughly from 1600 to 1750, was marked by profound religious, political, and social shifts. In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church mounted the Counter-Reformation—a vigorous, calculated response to fortify its influence and appeal through the very heartstrings of human emotion.

Art became a vessel for renewal, a persuasive and dramatic medium to reinvigorate faith amongst the masses. The Council of Trent (1545-1563), encapsulating this directive, urged a religious art style that was emotionally engaging and clear in its storytelling.

Therefore, Baroque art, particularly within Catholic regions, was suffused with theatricality, designed to inspire awe and devotion in the beholder and to act as an instrument of religious fervor.

Simultaneously, the rise of absolutism in the political realm contributed to the tenor of Baroque art. Monarchs like Louis XIV of France employed it as an indulgent, visual testament to their divine right to rule.

The grandeur of Baroque reflected a society in which the nobility and the church held supreme power and wealth, and art endorsed this stratification. The elaborately ornate palaces and churches, adorned with bold sculptures, lavish paintings, and intricate architectonics, stood as testaments to a hierarchical, controlled order—a mirror of the sovereign cosmos it sought to emulate.

Scientific exploration and discoveries of the time profoundly influenced the mindset of society and, in turn, the nature of its artistic output. The fresh understanding of light, space, and human anatomy—ushered in by advancements in science and exploration—infused Baroque art with novel forms of realism and a masterful play of chiaroscuro.

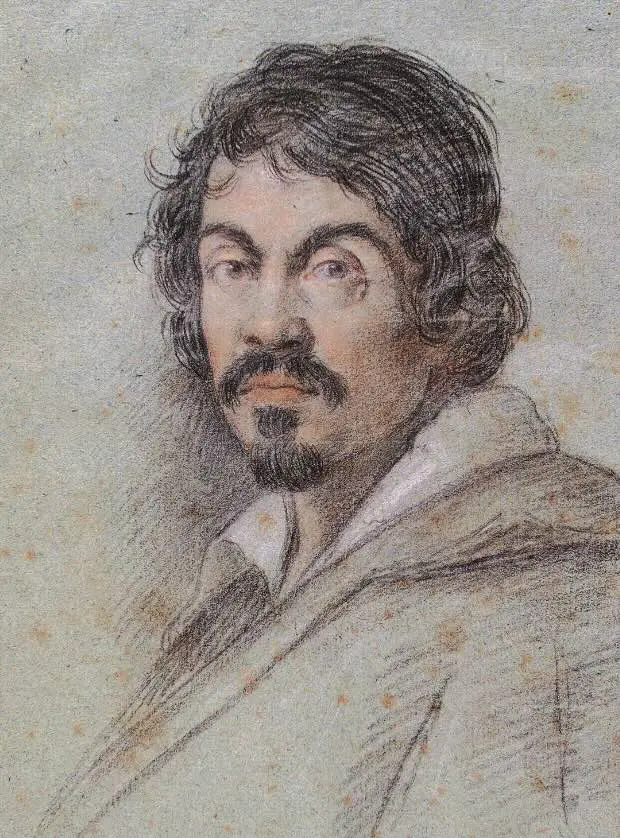

The play of light and shadow, so central to Caravaggio’s canvases, not only manifested the potency of the tenebrist style but also became symbolic of the underlying search for truth and the dichotomy between certainty and doubt in an evolving world.

Economic fluctuations shaped Baroque art, as well. As wealth generated by trade and colonial expansion flowed into Europe, especially in maritime powers like the Dutch Republic, art markets flourished, leading to genre painting and still life—forms catering to the tastes and curiosities of the burgeoning middle class.

Furthermore, the era’s individualism, personalized emotion, and the value placed on the dramatic and the monumental are all hallmarks of the Baroque art movement. This sense of movement and passion swept across the canvas and stone, echoing the dynamic currents that animated the historical backdrop of the time.

Artists like Bernini, with his kinetic sculptures, and Peter Paul Rubens, with his voluptuous, motion-filled paintings, encapsulated an age that was, above all else, about dynamism, power, and a compelling blend of reality and spectacle.

In essence, Baroque art was more than a simple product of its time—a bold exclamation, an era’s soul cast in light, shadow, and color, a reflection of the vibrant, throbbing life it sought to encompass. As the Baroque pearl found its luster in the gritty sands of historical strife and splendor, so did Baroque art’s defining brilliance in the crucible of its dynamic age.

Essential Formal Qualities of Baroque Art

The expansive canvas of Baroque artistry is characterized by an unapologetic boldness and complexity that reflects much of the era’s exhilarating spirit. Zeroing in on the formal elements, we find a language of form and aesthetics that is as vivid and evocative as the age itself.

At the very heart of Baroque art lies an incredible mastery over light and shadow—chiaroscuro. This technique is not merely a means of rendering form; it is a dramatic tool that sculpts scenes with utmost intensity and contrast, plunging them into a play of illumination that guides the viewer’s eye and emotions.

Paintings by Caravaggio are exemplary, wielding light with the precision and impact of a stage director, conjuring sight and sentiment exquisitely.

Closely linked to chiaroscuro is the equally striking technique of tenebrism. It pushes the envelope further by using stark contrasts, often submerging much of the composition in shadow to bathe critical elements in a near-divine spotlight. This selective illumination heightens the emotional pitch and lends scenes an unparalleled depth and mystery.

Moving beyond the manipulation of light, Baroque art thrives on vibrant colors. Rather than the restrained palette of earlier periods, Baroque artists opt for sumptuous, saturated hues. These colors do not merely please the eye but participate actively in the storytelling, carrying symbolic significance or denoting emotional undercurrents.

Compositions in Baroque artworks are rarely stagnant. Instead, they are charged with sweeping movement, twisting figures, and spiraling designs, leading the eye to a dynamic visual journey. This pulsating energy is often achieved through curvilinear forms and spirals—evident in the undulating lines of Bernini’s sculptures and the compositional whirls in Peter Paul Rubens’s paintings.

The element of space in Baroque art is another representative marker. Instead of flat or linear perspectives, Baroque compositions opt for deep, multidimensional spaces that invite viewers to step into the scene. This depth is achieved through complex, often diagonal compositions that recede into the background and foreshortening techniques that project forms toward the viewer—creating an effect of immediacy and involvement.

Detail and ornamentation in Baroque artworks are feats of meticulous craftsmanship and representational exuberance. From the intricately carved frames of paintings to the opulent decor of the surroundings, artworks revel in complex details that underline luxury and abundance.

Lastly, scale plays a crucial role in the Baroque lexicon. Many artworks, murals, and edifices embody an overwhelming size and scope that command attention and evoke a sense of the sublime. Such monumental proportions align with the Baroque affection for grandeur and the desires of patrons to impress and overwhelm.

These formal elements—chiaroscuro, tenebrism, vibrant color, movement, space, detail, and grand scale—combine to create Baroque art’s abundant tapestry. They serve as silent but expressive narrators who recount tales of an age where art was not just seen but deeply felt and experienced with the full force of human sensation and wonder.

Baroque Artists and Their Masterpieces

Within the grand and dramatic oeuvre of Baroque art lies a distinct language characterized by intense chiaroscuro, a technique that significantly contributed to the narrative intensity of paintings.

Famous for their ability to manipulate light and shadow, Baroque artists cast dramatic illumination across their canvases, creating a visual dichotomy that highlights the emotional crux of their subjects.

This method was not merely a stylistic preference; it was their way of guiding the viewer’s emotional response, setting a visual stage for the unfolding of human drama.

Tenebrism, closely associated with the great Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, took chiaroscuro to a new zenith. Caravaggio’s employment of stark, often almost theatrical, contrasts between darkness and blinding light intensifies the emotional gravity of his works.

His iconic “The Calling of Saint Matthew” showcases his command over selective illumination, with beams of light casting moral and narrative illumination upon his protagonists and their pivotal choices.

The vivacity of Baroque is also expressed through its palette. The era’s artists reached for sumptuous and saturated hues, which they employed with a boldness matched only by the drama of their compositions.

Artists like Peter Paul Rubens brought life and flesh to their vivid depictions of mythological and religious scenes, showcasing their skill through dynamic works such as “The Consequences of War.”

A palpable sense of movement pervades Baroque compositions, with figures often captured in mid-action, lending a kinetic quality to the painted scenes. Rubens exemplified this, crafting works imbued with a dynamic rhythm, his figures seeming to dance across the canvas in a choreography of draped fabric and exuberant gesture.

Baroque remains a testament to a period when art was both a mirror to the tumultuous world and an unyielding beacon of human expression, a tradition shaped by visionaries whose legacies continue to resonate in art’s expansive history.

Baroque Art: Variations Across Europe

While the overarching characteristics of Baroque art — its grandiosity, detail, and vibrancy — find common ground across European nations, its manifestations varied greatly, influenced by localized tastes, traditions, and varying interpretations of the Baroque ethos.

In Italy, the cradle of the Baroque, artists such as Bernini and Caravaggio pushed the boundaries of sculptural and pictorial drama. Baroque in Italy was synonymous with the spectacle — swirling draperies, lifelike figures, and theatrical presentations that leaped from the canvas and marble.

This was a response not only to the aesthetic preferences of the time but also to the call of the Catholic Church to entice visual narratives that communicated religious stories and values to the faithful.

On the other hand, Baroque in France was marked by a distinct air of classicism, an embodiment of control and harmony that aligned with the grandeur of the age of Louis XIV. The French Baroque, through the likes of Nicolas Poussin, emphasized order, a clear delineation of space, and a subdued version of the dramatics seen in Italian works.

The Palace of Versailles stands as a testament to the monumental scale and controlled opulence favored by the French interpretation of Baroque.

The Dutch Republic, with its Protestant moorings, had a more sober take on Baroque art. Here, it translated into deeply intimate and detailed genre scenes, still-lifes, and portraits.

Painters like Vermeer and Rembrandt van Rijn reflected Baroque principles through their expert handling of light and shadow, but often within the confines of ordinary life and in the service of a middle-class clientele. This fostered a more restrained Baroque, albeit rich in emotion and psychological depth.

In Spain, the Baroque took a decidedly intense and spiritual cast. The Spanish penchant for mysticism and the reflective spirit of the Counter-Reformation breathed life into the intensely devotional works of Francisco de Zurbarán and the hauntingly evocative canvases of Diego Velázquez. Spanish Baroque art carried a gravitas consistent with deep religious contemplation and royal patronage.

The Flemish region, through Peter Paul Rubens, offered a dynamic and sensual Baroque. Rubens’ exuberant, fleshy figures convey a vitality that delivers dramatic narratives with a visceral power. His canvases are a mélange of the tactile and the vivid, a Baroque concerned with the human form in its most robust and lively representation.

The Baroque era was a pan-European phenomenon. Still, its multifaceted presence across the continent can be appreciated only by diving deeply into the local contexts that shaped its distinct flavors.

From Spain’s spiritual intensity to France’s grand classicism, the enduring legacy of Baroque is that of a deeply human, profoundly expressive artistic period that, while sharing an everyday heartbeat, beat different rhythms across Europe.

Influence and Legacy of Baroque Art

The Enduring Impact of Baroque Art on Later Artistic Movements

Baroque art, originating in early 17th-century Europe, has cast a long and abundant shadow over subsequent art movements, injecting a heritage of stylistic innovations and thematic complexities that resonate through the annals of art history.

The Rococo movement, emerging in France during the early 18th century, can be considered a whimsical offspring of Baroque art. It adopted the exuberance of Baroque but channeled it into more playful and ornate aesthetics.

The grandeur and pomp of Baroque art were refined into the pastel tones and lighter elements of Rococo, with its asymmetrical designs and flirtatious curves echoing the Baroque’s initial departure from strict classical norms.

As the pendulum of taste swung from the ornate to the pure, Neoclassicism surfaced as a reaction to the Baroque and Rococo’s lavishness. Yet, even here, the influence of Baroque is seen in the dramatic use of light and space, now realigned with the harmony and proportion inspired by the art of ancient Greece and Rome.

Romanticism—emphasizing emotion, individualism, and nature—diverged significantly from the Neoclassical approach yet found common ground with the Baroque in celebrating the dynamic and sublime.

Romantic artists revived Baroque’s dramatic light and shadow to change landscapes and historical scenes with emotion, exemplified in the tempestuous seascapes of J.M.W. Turner and the brooding skies of Caspar David Friedrich.

The lineage of influence extends further to 19th-century Realism, where artists, much like their Baroque predecessors, sought to depict reality without embellishment. Yet, the Baroque’s penchant for naturalism—capturing the visceral textures of life—found renewed expression in the works of Realist artists like Gustave Courbet.

Baroque’s manipulations of space and light also reach into the evolution of the Impressionist movement, as these artists broke down the traditional techniques of shading and detailing to reconstruct reality using pure color. The Baroque influence subtly infiltrates their depictions of fleeting moments, and the focus on capturing the effects of light can be seen as an echo of Baroque spatial explorations.

Baroque art’s bold drama and emotiveness reverberated to the 20th century, informing the theatrical compositions of Expressionism—where emotional resonance was paramount—and continued to leave its mark on the grand gestures and spatial dynamics in Abstract Expressionism.

Baroque art’s emphasis on contrast and detail provided formative ground for Art Nouveau and the later Art Deco, translating the ornate and intricate into designs and motifs for a modernizing world. Even the maximalist tendencies in today’s Contemporary art find a distant relative in the Baroque’s love for the grand and the ornamental.

Whether consciously adopted or subtly integrated, the aspects of Baroque art—from its dramatic light and shadow to the emotional intensity of its subject matter—have provided a robust foundation upon which countless artists have constructed and deconstructed creative paradigms.

In essence, Baroque has offered a lexicon of artistic vocabulary that continues to enrich the dialogue between the past and the present, proving itself as an eternal touchstone in the ever-evolving narrative of art.

Baroque art’s elaborate tapestry of light, color, and emotion left an indelible mark shaping the contours of visual creativity for centuries to come.

Through emulating natural motion, embracing overwhelming sensations, and delivering profound narratives, the masters of Baroque did not just create art—they created a language of drama and excess that continues to echo across time.

As the lights of Bernini’s sculptures continue to flicker and Caravaggio’s painted shadows stretch into the modern age, the legacy of Baroque art endures, forever reminding us of the power of art to encapsulate the human experience in all its theatrical glory.

Anita Louise Art is dedicated to art education, great artists, and inspiring others to find and create their art. We love art that uplifts and inspires. #ArtToMakeYouSmile! #ArtToMakeYouHappy!

If you are interested to see any of my art, you can find out more by clicking here. If you are interested in what inspires me and my paintings, you can discover more by clicking here.

We have a free newsletter and would love you to be part of our community; you can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here. If you have any questions, I would be happy to talk to you at any time. You can reach me, Anita, by clicking here.

Subscribe to our Anita Louise Art YouTube Channel filled with great videos and information by clicking here.

Join us for our podcast “5 Minutes With Art.” Spend just 5 minutes a week with us to discover and learn about great art and artists. You can find out more about our podcast by clicking here.

Related Questions

Why Did New Art Movements Develop In The Years Following World War 1?

Many of the art movements after World War 1 came about as a direct protest about the devastation and loss of human life in the First World War. These art movements also included cultural and political movements where like-minded artists band together to produce satirical and other art.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Why Did New Art Movements Develop In The Years Following World War 1?.

What Are The Main Characteristics Of Minimalism Art?

Minimalism art started in New York City in the 1960s. The minimalist artist would use limit their use of lines, shapes, and colors in their art. The artwork had no trace of the artist’s emotions in the art. Minimalism art is considered an extreme form of abstract art. The most important geometric shapes in minimalism art are the square and rectangle.

You can discover more by reading What Are The Main Characteristics Of Minimalism Art? by clicking here.

How Do Art Movements Begin?

An art movement usually begins as a specific philosophy, goal, or objective that a group of typical artists have. This could include a standard belief system or a belief in a common style of art. An art movement usually changes the artistic direction of the artwork for its time.

You can learn more by reading How Do Art Movements Begin? by clicking here.