In a world wracked by the First World War’s unfathomable devastation, a new art movement emerged from the heart of Europe, not just to revolutionize the arts but to question the very fabric of society fundamentally. Dadaism, born amidst the chaos of 1916 in a neutral Zurich, was as much a cultural mutiny as it was an artistic revolution.

The movement surfaced as a visceral response to the horrors of war and a rebuke to the institutions that celebrated the rationality leading humanity to its destructive brink. Its essence encapsulated the absurd, the unpredictable, and the outright nonsensical, challenging every preconceived notion about art, expression, and the artist’s role in the tumult of the twentieth century.

Table of Contents

- Origins and Historical Context of Dadaism

- Key Characteristics and Techniques of Dada Art

- Influential Dada Artists and Their Contributions

- Dadaism’s Relevance in Today’s Artistic Discourse

- Related Questions

Origins and Historical Context of Dadaism

The Cauldron of Chaos: Dadaism’s Birth in the Trenches of World War I

As the echoes of World War I reverberated through the charred landscapes of Europe, a profound disillusionment with traditional values and aesthetic norms took root in the hearts of avant-garde artists.

This collective sense of despair and hatred towards the unprecedented destruction wrought by the war gave birth to an anarchic art movement known as Dadaism.

Dada—or Dadaism—emerged primarily in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1916, far from the front lines but deeply enmeshed in the psychological and cultural fallout of the conflict. It was a rebellion in both form and spirit. Artists associated with the movement, including Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Marcel Duchamp, sought to eradicate the foundations of the civilized society that had led to such catastrophic warfare.

The movement was a radical departure from anything seen in the art world. Dada ignored the very concept of traditional aesthetics; whether in poetry, visual arts, or performance, it thumbed its nose at coherent expression.

Where the world sought meaning and order, Dada flaunted chaos and irrationality. Collage, photomontage, and assemblage, often incorporating found objects and randomness, became the sacred techniques of the Dadaists, reflecting the disintegration of societal norms.

However, Dada was not just an artistic movement; it was a social commentary that condemned the nationalist and materialist values that led to mass destruction. Dada art is marked by its acerbic wit and satire, using the absurd as a weapon against the institutions that Dadaists saw as corrupt.

The infamous “Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp—a porcelain urinal presented as art—exemplifies this stance, challenging the definition of what could be considered art.

Moreover, the reach of Dada was transnational, spreading to Paris, Berlin, and beyond, as artists who were displaced by the war brought with them seeds of unrest that germinated in diverse art communities.

In Berlin, the movement took a more overtly political stance, where artists like George Grosz used their work to depict and criticize post-war societal issues, such as corruption and the rise of militarism.

Dadaism also paved the way for Surrealism and other modern art movements. Breaking down boundaries and encouraging the free association of ideas set the stage for a wave of artistic exploration and revolution that would ripple through the 20th century.

In sum, the massacre of World War I shattered the illusion of reason and progress that had dominated the European psyche. In its place, Dadaism arose as an artistic scream at night, a primal and often nonsensical protest against a world that had seemingly lost its sanity.

The movement’s legacy is a reminder that from the depths of destruction, new forms of expression and thought can rise—jarring, unexpected, and sometimes profoundly influential.

Key Characteristics and Techniques of Dada Art

Diving into the avant-garde waters of Dadaism reveals a fascinating tableau of techniques and features that sharply delineate Dada artworks from their artistic predecessors.

At the heart of Dada lies the inventive use of ready-made – everyday objects chosen by the artist and designated as art. This radical approach, exemplified by Marcel Duchamp, blurs the line between art and life, challenging the spectator to reconsider the essence of art itself.

Another hallmark of Dadaist works is the penchant for chance in the creative process. Artists such as Hans Arp employed techniques like random drop poetry or automatic drawing, relinquishing control and allowing the forces of chance to shape the outcome.

This unpredictability was not solely a creative choice but a philosophical stance reflecting Dada’s view of a world unhinged by war and irrationality.

Performance art found a fertile ground in Dada as well. Lounges and public gatherings became platforms for anti-art performances that combined poetry, visual arts, and theater.

The intention was to break the barrier between art and audience, often incorporating the latter into the act. Dada performances were intentionally provocative, seeking to jolt the observer out of passive consumption into active engagement.

Furthermore, sound poetry introduced a dynamic intersection between language and sonority within Dada art. For example, Kurt Schwitters’ “Ursonate” is a symphony of nonsensical sounds that challenge traditional linguistic structures, promoting the idea that meaning in art could be found in pure expression rather than conventional narratives.

Technical innovations also played a significant role in developing Dada’s aesthetic. The movement saw some of the first examples of artistic photomontage, where cut-up and rearranged photographs created new, often disorienting, context and meaning—a nod to the fragmented nature of post-war society and the possibilities inherent in new media.

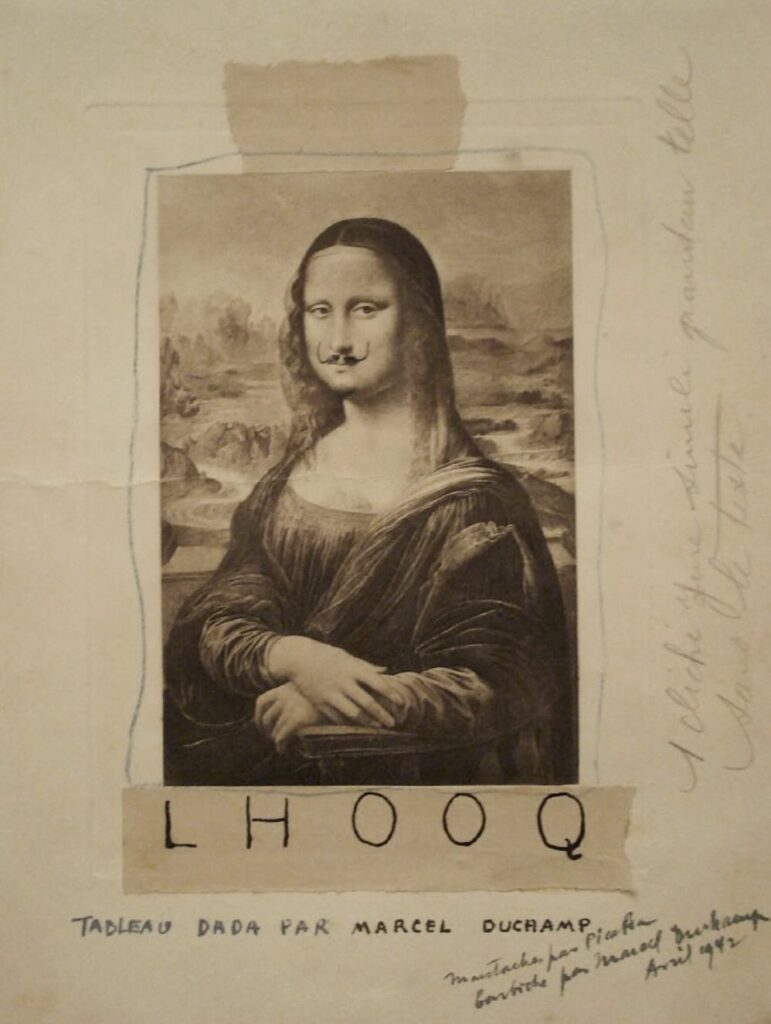

The conceptual approach in Dada art can also be seen as a prominent feature. Artworks were designed to exist as ideas rather than mere physical objects. This is seen most famously in Duchamp’s readymades, such as “L.H.O.O.Q.,” where the mere addition of a mustache to a postcard reproduction of the Mona Lisa becomes a powerful Dadaist statement.

Last but not least, Dadaists embraced absurdism, employing humor and nonsense to mock the supposed rationality that led to the catastrophic Great War. This irony was deeply rooted in the Dadaist approach to art-making, presenting works that seemed to laugh in the face of the absurdity of contemporary life.

In conclusion, Dadaism’s defiant spirit fostered a seismic shift in the arts through its revolutionary approaches, such as embracing readymades, adopting chance, integrating performance, experimenting with sound poetry, exploring montage, conceptualizing art, and invoking absurdist humor.

These techniques and features elucidate a movement that not only critiqued a world gone mad but also left an indelible mark on the canvas of art history.

Influential Dada Artists and Their Contributions

Central Figures of Dadaism: Torchbearers of the Avant-Garde

Dadaism, the cultural storm that swept through the 20th-century art world, gave rise to a pantheon of avant-garde provocateurs whose legacies continue to inform contemporary discourse. Let us delve into the luminary minds that steered this anti-establishment ethos, challenging the art world and ultimately reshaping it.

Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings stand as the progenitors of the Dada movement – their Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich serving as the embryonic chamber for Dada’s conception.

Ball’s manifestos articulated Dada’s dissonance with the cultural and political status quo, while Hennings’ performances infused the movement with a bohemian vitality. Their collaboration was foundational, planting the seed of dissent that would burgeon throughout Europe.

Tristan Tzara, the effervescent spirit of Dada, emerged as a pivotal voice, penning manifestos that crystallized Dada’s ethos. His poems, performances, and nonconformist publications amplified Dada’s resonance, reaching the heart of post-war disillusionment. Tzara’s relentless advocacy fostered pockets of Dada activity, particularly in Paris, where the movement’s incendiary torch was passed and fanned into a larger flame.

Hannah Höch, a central figure amidst Berlin Dadaists, challenged societal and gender norms through her cutting-edge photomontages, shining light on the fragmented reality of the modern world. Höch’s audacity laid bare the inherent contradictions and chaos of contemporary life, her collage aesthetics remaining seminal in the art that questions, rather than accepts, established paradigms.

Kurt Schwitters, operating on the fringes of official Dada circles, redefined the boundaries of mediums with his concept of “Merz.” His Merzbau installations prefigured immersive art experiences, allowing him to forge his legacy as an innovator of environmental art. Schwitters’ breadth of material exploration reflected Dada’s spirit through his lens, cementing him as an indispensable avant-gardist.

The enigmatic Francis Picabia traversed the landscape of Dadaism, sowing seeds of discord through his irreverent artworks and writings. His pivotal role in the Parisian Dada scene and later ventures into Surrealism marks a trajectory that embodies Dada’s fluid, often contradictory nature.

Man Ray transcended the confines of Dada with his innovative photographic techniques, namely the “rayograph,” which melded the movement’s love for accident with technical mastery. As much a facilitator of dialogues as an artist, his atelier became a nexus for Dada and Surrealist activity, bridging gaps between mediums, practices, and ideologies.

The legacies of these central figures are multifold – their radical reimaginations have sown the seeds for numerous contemporary movements. Be it the riotous energy of punk aesthetics, the conceptual rigor of minimalism, or the shock tactics employed in modern protest art, traces of Dada DNA are evident.

From subverting the gallery system to championing cultural détournement, the heartbeats of this motley crew pulsate through the myriad veins of today’s artistic expressions.

Dada’s progeny proves that creativity’s wellspring is eternal from the chasm left by destruction. The central figures of Dadaism – vibrant and fearless – have bestowed upon us a historical lineage where irreverence is intellect, and cultural critique is its form of poetry.

Their legacy endures as an affirmation: art is ever dynamic, reflective of the perpetual motion of human experience, and defiant against the rigid stones of tradition that attempt to impede its flow.

Dadaism’s Relevance in Today’s Artistic Discourse

In the milieu of the contemporary art scene, Dada’s profound impact continues to resonate, manifesting through a myriad of forms that challenge the status quo.

The essence of Dadaism, fiercely unapologetic and eternally avant-garde, finds its relevance in the current atmosphere of political and social upheaval that parallels the tumultuous periods it initially rebelled against.

The ready-made, today, is not merely a specific object but has expanded into a vast conceptual realm of found art and appropriation. Artists routinely dismantle existing narratives by recontextualizing everyday items, shifting the discourse from the object’s aesthetic value to its inherently provocative conceptual narrative.

Chance, once a revolutionary approach Dadaists used to circumvent reason, has been adopted by numerous contemporary artists to embrace unpredictability in the creative process. From algorithmic art to crowd-sourced projects, the principle of aleatory processes continues to defy conventional planning and reflect the complexity of the human condition.

With its roots tangled in Dada antics, performance art remains a potent medium for activists and artists. These live, transient experiences disrupt public spaces, dismantle the invisible fourth wall, and coax audiences into questioning their roles within the fabric of society.

As we dismantle linguistic barriers, Dada’s sound poetry, a celebration of anarchy in language, finds lineage in the experimental poetics of today, pushing the boundaries of communication and the expressiveness of the human voice beyond conventional syntax.

Technical innovations like photomontage have metamorphosed with the digital age. Contemporary artists harness cutting-edge tools to carve layered narratives, initiating dialogues across time and cultural divides.

The conceptual methodology honed by Dadaists, which heralded art as an idea rather than just a physical product, now underpins the work of conceptual artists, who strive to distill art into pure thought, often bypassing the tangible altogether.

Absurdism, humor, and cultural jamming resonate deeply within an age where satire becomes a weapon against authority and a tool to unravel the iron grip of rationality that often blinds society to its follies.

Artists of today, akin to Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, continue to construct spaces where the avant-garde thrives, repudiating conventional venues and crafting alternative platforms that echo the anarchistic spirit of Cabaret Voltaire.

Within the contemporary prism, the Dada aesthetic enlivens an entire spectrum of movements, from Neo-Dada to Fluxus, from Pop Art to Punk, each inheriting the torch of nonconformity and the zeal to visualize new worlds from the residue of the old.

The philosophies propagated by Tristan Tzara, Kurt Schwitters, and their contemporaries, crafted from the aftermath of chaos, have become a timeless repository, prompting artists to question, “What is art?” in an age where the very notion of reality is continually dissected and reassembled.

Hannah Höch and her kin’s piercing commentary on gender and societal expectations resound in the works of today’s artists, who use their media to confront taboos and dismantle oppressive frameworks that still loom over contemporary society.

Man Ray’s pioneering spirit continues to influence the oeuvre of those wielding cameras and digital tools, reminding us that art’s capability to capture, transform, and transcend the mundane remains boundless.

Dada’s subversive legacy, defiant and invincible, acts not only as a linchpin in the historical continuity of art but also as a call to arms, a defiant whisper that urges the artists of today to reassess, reinterpret, and revolutionize.

The spirit of Dadaism, echoing through the annals of history, remains a timeless reminder of the potent role of art in confronting and dissecting the complexities of human experience.

Just as the Dadaists once wielded their outrageous tactics to upend the status quo, contemporary voices harness similar strategies to scrutinize and reflect upon the dissonances of our present-day world.

Dada’s influence is indelibly etched into the DNA of modern creativity, empowering artists to reimagine the boundaries of the possible perpetually and to persistently engage in the essential dialogue with the ever-unraveling tapestry of society.

Anita Louise Art is dedicated to art education, great artists, and inspiring others to find and create their art. We love art that uplifts and inspires. #ArtToMakeYouSmile! #ArtToMakeYouHappy!

If you are interested to see any of my art, you can find out more by clicking here. If you are interested in what inspires me and my paintings, you can discover more by clicking here.

We have a free newsletter and would love you to be part of our community; you can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here. If you have any questions, I would be happy to talk to you anytime. You can reach me, Anita, by clicking here.

Subscribe to our Anita Louise Art YouTube Channel filled with great videos and information by clicking here.

Join us for our podcast “5 Minutes With Art.” Spend just 5 minutes a week with us to discover and learn about great art and artists. You can find out more about our podcast by clicking here.

Related Questions

Louvre Museum Facts, Our Top 7 Facts

The Louvre is the largest museum globally; it was once built as a fortress to protect the city of Paris. Under the French Republic’s rule, General Napoleon expanded the Louvre’s collections. One of the most important paintings at the Louvre is the Mona Lisa painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

By clicking here, you can discover more by reading Louvre Museum Facts, Our Top 7 Facts.

11 Interesting Facts About Traditional Hawaiian Art

Hawaiian art is divided into three main periods: pre-European art, Nonnative Hawaiian Art, and Hawaiian Art With Western Influences. After Captain Cook arrived in Hawaii in 1773, traditional Hawaiian art changed as Western culture influenced Hawaiian art. The Volcano School of Art was developed in Hawaii in the late 1800s when the artist’s work became impacted by the live volcanic eruptions in Hawaii.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading 11 Interesting Facts About Traditional Hawaiian Art.

Am I Too Old To Start Oil Painting?

You are never too old to learn to oil paint. You can start to oil paint at any age. If Grandma Moses could learn to paint at age 78, then she set an example for us all – that you are never too old to learn to paint. There are some advantages to learning to paint when you are older vs. younger.

By clicking here, you can discover more by reading Am I Too Old To Start Oil Painting?