In the waning embers of the medieval era, an intellectual and cultural revival began to stir within the heart of Europe, setting the stage for a period known as the Renaissance. The very essence of this revival was marked by a profound reconnection with the classical past, heralding the dawn of a new age in which art, science, and scholarship would flourish.

With vibrant city-states like Florence and Venice at its helm, this cultural phenomenon embraced the might of humanism, catalyzed by the fall of Constantinople and the precious ancient texts it brought to light. Moving beyond the confines of the Dark Ages, this transformative epoch witnessed socioeconomic transformations that nourished the soil from which the Renaissance would spectacularly bloom.

Table of Contents

- Origins of the Renaissance

- The High Renaissance and Cultural Icons

- Renaissance Spread Across Europe

- Legacy and Influence of the Renaissance

- Related Questions

Origins of the Renaissance

Renaissance: Emergence from the Medieval Cocoon

As the Medieval epoch waned into the annals of history, the dawn of the Renaissance bestrode Europe with a brilliance that still dazzles the collective imagination. This era, christened “Renaissance,” meaning rebirth, was a profound awakening from what many consider the prolonged slumber of the Middle Ages.

The metamorphosis into the cultural, artistic, and educational efflorescence that characterized the Renaissance was neither sudden nor accidental but a gradual unfurling of human potential and intellectuality.

The seeds of this phenomenal intellectual rebirth lay partly within the very fabric of the Medieval era. Acknowledging that the Middle Ages, often unfairly dubbed the ‘Dark Ages,’ hosted many monastic scholars and visionary artisans is imperative.

These often overlooked figures preserved the ancient texts and wisdom that would later fuel the Renaissance’s intellectual fires.

The key to understanding this transition lies in what was preserved and how it was reinterpreted and expanded upon. A renewed fascination with humanism—human beings’ innate value and potential—shifted focus from the spiritual to the secular.

This human-centric philosophy was spawned by the contemplation of classical antiquity texts, a process enabled by the increased availability of literature following the remarkable invention of Gutenberg’s printing press in the 15th century.

Economically, the ascendance of the merchant class created an environment ripe for cultural and intellectual investment. Affluence allowed these burgeoning capitalists to become patrons of the arts, endorsing creatives who would push boundaries and breathe life into new ideas.

Banking families like the Medici of Florence supported artists and scholars, thus melding artistic and intellectual pursuits.

Concurrently, the very fabric of thought was altered. Medieval scholasticism, which heavily relied on Aristotelian logic and Christian theology, began to contend with the empirical method.

Pioneers like Leonardo da Vinci, who dissected cadavers against the epoch’s conventions, embodied this rigorous curiosity. This penchant for empirical evidence sowed the seeds for modern-day scientific methodology.

It is also paramount to recognize the geopolitics that inadvertently fostered this rebirth. The fall of Constantinople in 1453, for instance, spurred Greek scholars to migrate west, bringing classical texts previously inaccessible to Western Europe. This infusion of classical knowledge kindled an insatiable thirst for the wisdom of ancient Greece and Rome, manifesting in every facet of Renaissance culture.

As the canvas of the Renaissance was colored by such diverse and profound influences, it swelled into an intellectual blossoming unparalleled in its breadth and depth. The period was marked by a symmetry of the sciences and the arts, with polymaths like Michelangelo exemplifying the seamless blend between physical anatomy understanding and sculptural genius.

Architecture tore away from the Gothic and grew wings with Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence. Literature found its vernacular voice in Dante’s “Divine Comedy” and reached full expression in Shakespeare’s plays. Indeed, every dimension of human capability seemed to expand during the Renaissance.

The spirit of the Renaissance, thus, was the entwined dance of intellect and artistry, with each discipline enriching the other. Out of the distant echoes of medieval chants arose the symphonies of Monteverdi, just as the dimly-lit corridors of gothic cathedrals parted for the luminescence of Raphael’s paintings.

Galileo’s lens to the heavens and Machiavelli’s pen delving into political strategy marked the same unquenchable desire to understand, express, and transcend human experience.

In recollecting how the Renaissance burgeoned from the Medieval era, one encounters a stirring realization: it was an epoch not of abrupt change but of awakening, where human thought unfurled its wings and soared towards the unfathomable heights of potential.

The Renaissance is an immortal testament to what can be achieved when the curious intellect and the creative spirit join hands to explore the boundless landscapes of possibility.

The High Renaissance and Cultural Icons

Forging ahead into the heart of the Renaissance, the luminary figures who epitomized its artistry and intellectual endeavors emerge with a clarity that belies the centuries that separate us. These ideals not only harnessed the zeitgeist of their times but also molded the contours of Western art for generations to follow.

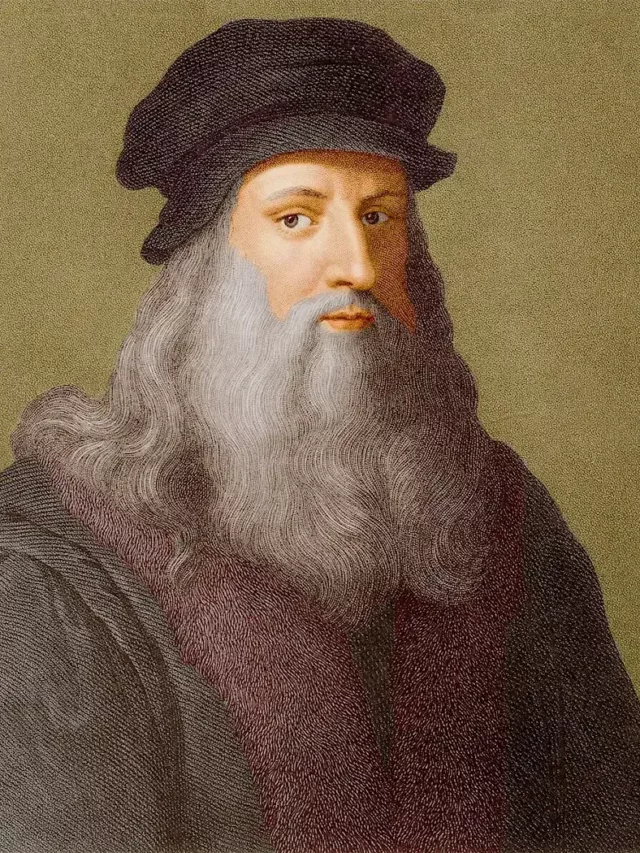

Chief amongst these trailblazers was Leonardo da Vinci, an archetype of the Renaissance Man. With an intellect as voracious as his talent, Leonardo’s ventures spanned across painting, anatomy, engineering, and botany.

His works, such as the enigmatic “Mona Lisa” and the divine “The Last Supper,” are not merely masterpieces of human expression; they represent the pinnacle of combining empirical observation with artistic beauty. His meticulous studies of the human body and his pioneering use of sfumato—a technique allowing tones and colors to shade gradually into one another—radiate the ethos of the Renaissance.

Equally formidable was Michelangelo Buonarroti, a maestro of marble whose sculptures like “David” and “Pieta” capture human beauty in its most sublime form.

Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel are a testament to the incandescent brilliance of an artist who sought to touch the divine. The impeccable anatomy, the dynamic composition, and the profound storytelling fostered a narrative vitality that annulled the boundaries of mere fresco technique.

Raphael Sanzio, another pillar of the High Renaissance, bestowed grace and elegance upon the art world. In works like “The School of Athens,” Raphael depicted the great philosophers of antiquity and infused the canvas with harmony and perspective—an embodiment of the intellectual and artistic synthesis. His ability to create softer expressions and his use of perspective were innovations that enhanced the vividness and emotional resonance of visual storytelling.

With his elongated figures and emphasis on Mannerism, Parmigianino later incorporated the ideals of the Renaissance into a more personal and stylized art form. His “Madonna with the Long Neck” is an ode to the newfound freedoms artists discovered in moving away from strict religious constraints, highlighting a transition toward a more abstract and expressive aesthetic.

The Venetian titan, Titian, known for his supreme handling of color, broadened the palette of Renaissance art. Through works like “Assumption of the Virgin,” Titian revolutionized oil paint’s potential and inspired a more sensual and vibrant expressionism that foreshadowed the lush palettes of later movements.

Lastly, the Northern Renaissance offered its prodigies, such as Albrecht Dürer. Dürer was a bridge between the Italian influence and the distinct, detail-rich tradition of the North. His masterful woodcuts and engravings, like “Melencolia I,” convey a depth of intellectual and spiritual introspection, entwining the aesthetic with the metaphysical.

Thus, the quintessential contributors to Renaissance art left an indelible legacy. Their unprecedented contributions—ranging from the refinement of realistic depiction and perspective in painting to the elevation of sculpture as a medium for exploring humanist ideals to innovative techniques in printmaking—have imprinted themselves upon the tapestry of art history.

The Renaissance’s paragons laid the groundwork for an ever-evolving discourse in aesthetics that still prevails, a living testament to their enduring vision and genius. In their hands, art was not just a mirror to nature but a crucible for the profound alchemy of human imagination and reality’s raw beauty.

Renaissance Spread Across Europe

The efflorescence of the Renaissance did not occur in isolation but rather through a vigorous cross-pollination of ideals and aesthetics, which, much like tendrils, extended their reach across Europe, imbuing the continent with renewed spirit and grandeur.

Architects and artists traveled not only for work but also propelled by an intrinsic yearning for knowledge across diverse territories, imparting their skills and absorbing new influences.

Italian maestros were not siloed geniuses; they frequently entertained discourse with luminaries and patrons across the continent. Leonardo da Vinci’s fabled notebooks reveal not merely the intensity of his anatomical and engineering investigations but also bear witness to a multitude of dialogues with leading philosophers and scientists, thereby nurturing a shared ethos of inquiry.

Meanwhile, Michelangelo’s Herculean efforts redefined the aesthetics of the sacred; his figures on the Sistine Chapel ceiling reflect an intellectual syncretism, marrying biblical storytelling with a humanistic embodiment of divine figures.

Raphael’s contribution was no less significant, for his art captivated the imagination by harmonizing space and form. “The School of Athens” serves as a poignant emblem of this integration, where a fictive congregation of philosophers encapsulates the essence of knowledge propagation, a meta-commentary on the Renaissance itself.

As these larger-than-life figures set the benchmark, regions beyond Italy quickly fashioned their vernacular idioms. Parmigianino’s “Madonna with the Long Neck,” with its swooning elegance, inspired the Mannerist movement, which, while anchored in classical ideals, sought to infuse the art with a discernible tension and dynamism, stretching the boundaries of form and posture.

Up North, the Renaissance emanated a different aura, imbued with keen attention to naturalistic detail and texture. Titian’s breakthroughs in color application influenced Venetian painting and informed the broader spectrum of European art, marking a departure from the tonal rigidity that characterized earlier works.

Albrecht Dürer is a titanic figure bridging the Italian Renaissance with the Northern sensibility. His woodcuts and engravings connected the visual narratives and meticulous craftsmanship of the North with the proportional elegance and humanistic values championed by the South, creating a lingua franca that resonated throughout Europe.

Through the hands of these and other artists, the Renaissance enriched the visual language of art, introducing a new lexis of perspective, anatomy, and affect. The proliferation of tangible realism, the perfected use of chiaroscuro, and the refinement of oil painting techniques solidified a legacy of technical advancements.

The enduring legacy of Renaissance art serves as a lodestar in art history, perpetually guiding future generations to revisit the wellspring of creativity from which modern aesthetics arose.

The fluid exchange of ideas that characterized the period is a reminder that art is inextricably linked to the flow of culture and thought—a testament to the Renaissance as a living history that continues to inform and shape the discourse of aesthetics and artistry.

Legacy and Influence of the Renaissance

The Renaissance era, an epoch of monumental change and brilliance in art and culture, continues to vibrate through the corridors of time, touching and influencing contemporary artistic expressions in manifold ways. Its resonances can be traced through the fundamental principles and enduring innovations crystallized during that age.

Firstly, drawing from live models, a Renaissance development, remains central to artistic training today. This enriched the fidelity of figure painting and underscored the importance of direct observation in art.

The profound studies of anatomy by artists like Leonardo da Vinci and his contemporaries impart to modern artists the same reverence for the human form and its sophisticated depiction, enhancing the realism that can be achieved on canvas or through sculpture.

Furthermore, the principles of linear perspective, perfected during the Renaissance, serve as the bedrock for rendering space and depth. Whether in fine art, illustration, or digital media, creating the illusion of three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface is an invaluable skill that finds its roots in the geometric experiments of Renaissance masters.

The Renaissance also led to an enriched dialogue between art and its patrons, which is evident today in commission-based works and collaborations. Modern artists often engage with clients and benefactors in a symbiosis reminiscent of the flourishing relationships between Renaissance artists and their wealthy sponsors.

This synergy not only supports the financial backing of contemporary art but also invites a dynamic interaction of ideas and perspectives.

The concept of the artist as a solitary genius, a notion popularized in the Renaissance, persists in how society views art creators today. The iconic stature of figures like Michelangelo, celebrated for his astounding individual talent, has helped shape the public perception of the artist as a visionary capable of rendering humanity’s deepest aspirations and most profound stories into palpable forms.

The vibrant experimentation with oil painting during the Renaissance, which led to richer color palettes and varied textures, can be seen in the vast array of materials and techniques artists harness now.

The luminous layers and versatility that oils allowed gave birth to an endless pursuit of visual effects and finishings that transcend time, from the impasto strokes of Vincent van Gogh to the vast, color-field canvases of Mark Rothko.

In education and theory, the revival of interest in the classical ideas of beauty and proportion during the Renaissance, as epitomized by Vitruvius’s treatises, has contributed to the aesthetic framework used by art historians and theorists. The lexicon developed to analyze and appreciate art leans heavily on the concepts and terms sculpted during that era.

Last but not least, the democratization of art, initiated by the distribution power of the printing press in the Renaissance, has expanded exponentially with the rise of digital media.

Artistic expression and knowledge that were once the province of the elite are now widely accessible, echoing the egalitarian aspirations of Renaissance humanism.

In tracing the lineage of today’s art back to the Renaissance, one sees not a thread but a tapestry—woven meticulously over centuries, its patterns and colors informing the present.

Renaissance ideals of beauty, technique, and expression continue to inform contemporary practice, ensuring that the era’s magnificent vision of art’s potential remains as vibrant and impactful today as it was over five hundred years ago.

Reflection upon the Renaissance reveals the indelible blueprint it left on the warp and weft of modern civilization.

The period’s artistic and intellectual trailblazers forged a legacy that resonates through contemporary culture’s corridors, influencing the way we perceive the world around us.

From the proportional grace found in modern architecture to the narrative depth of cinema, the echoes of Renaissance humanism and realism can be discerned. In peering back at this luminous chapter of history, one gains a profound appreciation for the enduring wisdom and creativity of an era whose influence continues to shape the human experience across the globe.

Anita Louise Art is dedicated to art education, great artists, and inspiring others to find and create their art. We love art that uplifts and inspires. #ArtToMakeYouSmile! #ArtToMakeYouHappy!

If you are interested to see any of my art, you can find out more by clicking here. If you are interested in what inspires me and my paintings, you can discover more by clicking here.

We have a free newsletter and would love you to be part of our community; you can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here. If you have any questions, I would be happy to talk to you anytime. You can reach me, Anita, by clicking here.

Subscribe to our Anita Louise Art YouTube Channel with great videos and information by clicking here.

Join us for our podcast “5 Minutes With Art.” Spend just 5 minutes a week with us to discover and learn about great art and artists. You can find out more about our podcast by clicking here.

Related Questions

The Top 12 Italian Painters Of All Time

Our Top 12 Italian painters include such famous and well-known names as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael. Still, it also has many other names, such as Caravaggio and Sandro Botticelli, which are also crucial for Italian art.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading The Top 12 Italian Painters Of All Time.

10 Emotionally Powerful Paintings

Throughout the world, artists have given us many emotional paintings. Whether it was their own emotions, they were feeling, as in The Scream by Edvard Munch, or through a Biblical story as The Prodigal Son By Rembrandt.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading 10 Emotionally Powerful Paintings.

What Are The Most Beautiful Pieces Of Art In The World?

Art is one of the most subjective things in the world; what one person loves, another person may hate. To look at what we consider to be the most beautiful pieces of art in the world, we also look at the most famous paintings.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading What Are The Most Beautiful Pieces Of Art In The World?