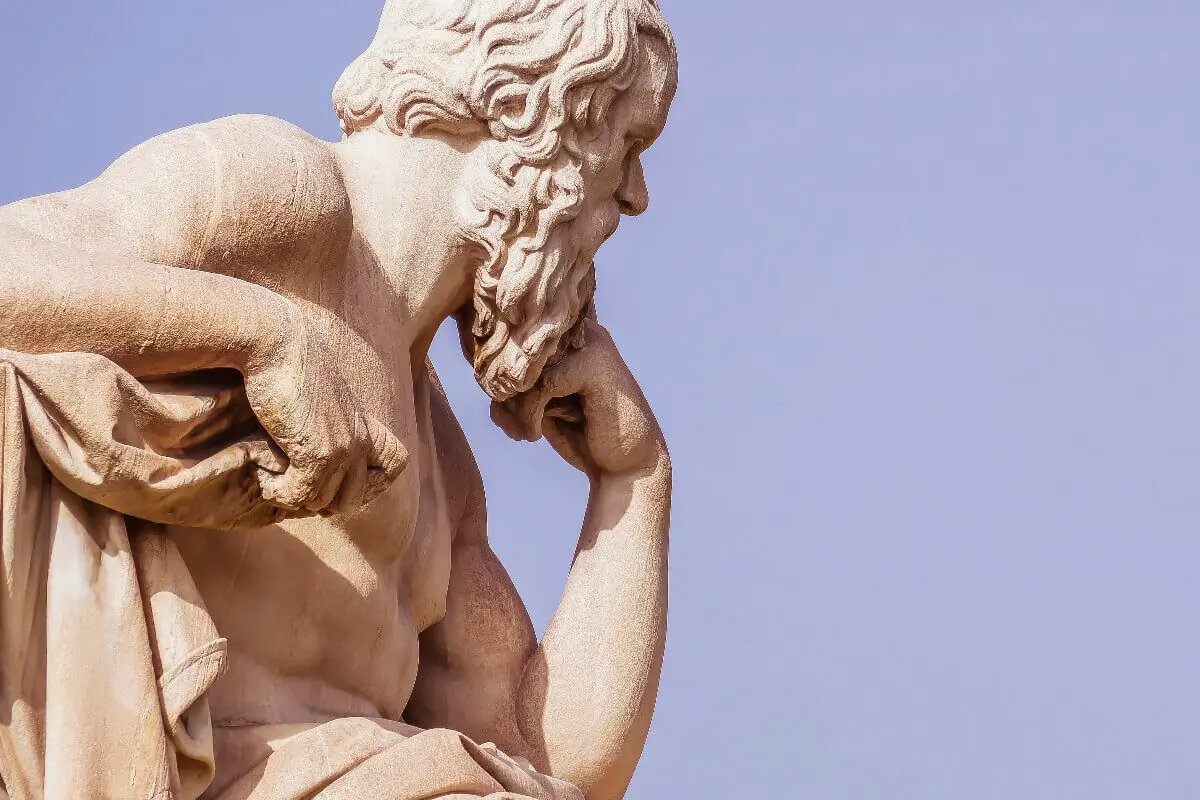

The pantheon of ancient Greek sculpture stands as a sentinel to the brilliance and ingenuity of human creativity, weaving a narrative that extends from the Archaic period’s rigid forms to the Hellenistic era’s dynamic expressions. Within this artistic odyssey, we uncover the evolution of an art form that has profoundly influenced the cultural tapestry of humanity.

This essay journeys through time, discovering how the Greeks sculpted not only marble and bronze but also the very aesthetics of Western civilization. As we traverse the storied past of this magnificent art, we encounter the evolution of style, the meticulous techniques of creation, and the unparalleled masterpieces that continue to echo through the ages.

Table of Contents

- Historical Context and Evolution

- Major Styles and Periods

- Iconic Works and Artists

- Sculpture Techniques and Materials

- Conservation and Display

- Related Questions

Historical Context and Evolution

The Chisel and the Polis: Historical Forces Sculpting Ancient Greek Art

In the annals of art history, few periods command as much admiration and intrigue as the epoch of ancient Greece. Here, the sculptor’s hand was guided not only by a deep understanding of human anatomy and aesthetic ideals but also by the tumultuous undercurrents of history.

To truly appreciate the grandeur of ancient Greek sculpture, one must delve into the substance of the past and unravel how historical events carved their indelible marks upon marble and bronze.

In ancient Greece, sculpture was the silent witness to the relentless progress of human endeavors. It stood as an enduring record, a testimony to the triumphs and tragedies that shaped a civilization rooted in democracy, philosophy, and the pursuit of beauty.

The prevailing political, social, and religious events were inextricably linked to this art form’s evolution, influencing its function and very essence.

The Archaic era (circa 800-500 BCE) laid the cornerstone for this artistic journey. During this time, Greece was a patchwork of city-states, each fiercely independent yet bound to one another through shared language, religion, and culture.

It was an age of colonization and expansion, allowing for a cross-pollination of ideas with other Mediterranean cultures. The kouros and kore statues – depicting idealized young males and females – emerged in this era, still tethered to Egyptian rigidity yet yearning for something distinctively Hellenic: a future where form harmonizes with spirit and movement.

The tumult of the Persian Wars (between 499 and 449 BCE) marked a transformative chapter in the Greek narrative, bolstering the community spirit and fostering a buoyant sense of self. In the wake of these conflicts, the Classical period flourished, and with it, sculpture assumed a new dynamism and anatomical precision.

The contrapposto stance, an innovation embodying balance and motion, became a hallmark of the time. Masterpieces like the Discobolus and the bronze charioteer of Delphi epitomize the harmony and proportion that characterized the ethos of a society striving toward the ideal.

As Greece entered the fourth century BCE, so did its art enter the Late Classical phase. This era was marred by internal strife and the Peloponnesian War’s devastation—an internecine conflict that pitted Athens against Sparta and left soul-deep lacerations upon the Greek world.

In sculpture, the vitality of prior years yielded sober reflection and a newfound exploration of emotional depth, seen in works like the sculptures of Praxiteles, which exude a serene, often introspective aesthetic.

The Hellenistic period (circa 323-31 BCE) it dawned amidst the ashes of Alexander the Great’s expansive but short-lived empire. It was a time of cultural mingling and experimentation as Greek influence spread to the distant reaches of the known world.

Hellenistic sculpture is characterized by its dramatic expressiveness, intricate detail, and bold naturalism. The Laocoön Group exemplifies the heightened emotional intensity emblematic of this era, a luscious tapestry of agony and ecstasy that narrates the human condition with unprecedented poignancy.

Ancient Greek sculpture today is a sentinel of the outdated, echoing the whispers of history through its timeless forms. From the Archaic period’s humble beginnings to the Hellenistic age’s eclectic vigor, this artistic legacy reveals a tapestry of innovation shaped by the dynamism of political upheaval, social transformation, and religious ceremony.

The pulse of history courses through the marble veins and bronzed sinews of the Greek sculptural tradition, immortalizing the defining moments of the polis in each deliberate strike of the chisel.

Major Styles and Periods

Moving beyond the well-trodden paths of Hellenistic innovation and Classical refinement in Greek sculpture, it is crucial to comprehend how artists of ancient Greece distinguished their work through styles that responded to the evolving tastes and philosophies of their society.

While aesthetic principles undeniably evolved, specific characteristics in sculptural styles remain the touchstones of their respective periods, echoing the ideological landscape of ancient Greek life.

The Early Classical period, often hailed as the Severe Style phase, marks a transition from the rigidity of Archaic forms to the pursuit of ideal proportion and realism. During this era, sculptors broke away from the static poses of the kouros and kore figures, endowing their works with a newfound dynamism and emotional subtlety.

There’s a rationalization in structure and a quiet elegance that embodies the nascent spirit of democracy in the city-states, now reflected in the statues’ more humanized gaze and stances.

One prominent example of this transition is the shift in the representation of the human anatomy, where sculptors experimented with more accurate musculature and balanced proportions. This period is marked by a departure from the idealism that dominated the preceding eras to adopt a more naturalistic approach to capturing human form.

As such, it was a pivotal moment that laid the groundwork for the anatomical precision defining the Classical style.

The sculptural approach during the High Classical period epitomizes the zenith of aesthetic achievement, with artists bringing an unrivaled sense of harmony and balance to their work.

The canonical proportions developed during this time sought to imitate the human form and elevate it to an idealized state of balance and symmetry. This period is remarkably personified by the works of Polykleitos and Phidias, where the former’s Doryphoros—a canonical statue representing the perfect harmony of symmetry—ushered in an era of mathematical precision in artistic creation.

The subtleties between the Athens and Sparta sculptural styles during the Classical period are also worth noting. Athenian sculpture, undoubtedly represented by the Parthenon Marbles, mirrors the city’s philosophical and cultural climb to prominence, encapsulating it in the serene and idealized figures that adorn the Parthenon’s frieze.

Contrastingly, Spartan sculpture, although less prominent to the modern eye, honed a more austere and robust aesthetic in alignment with their aggressive and disciplined society.

Moreover, the Late Classical period moved towards personal, more individualized expressions. This is especially evident in sculptures depicting the human interaction with the divine and the emergence of lush, more sensual renderings of clothing and hair, as seen in the works attributed to Scopas and Lysippos, who further pushed the boundaries of expressiveness and natural movement.

Unveiling a different facet, the Macedonian conquest under Alexander the Great opened doors to cross-cultural artistic influences that would deeply imprint upon the Hellenistic style.

Here is seen an unprecedented embrace of eclecticism—ranging from the celebration of youthful athleticism to the poignant depictions of age and the grotesque—brought to life with an intensity and virtuosity that elevated the narrative drive of sculpture.

The dynamic qualities that characterize the Hellenistic period, such as the pathos captured in the furrowed brows and contorted limbs, marked a definitive shift from the poise and restraint of previous periods.

To appreciate ancient Greek sculpture solely through the lens of their eras would be to miss the undercurrents of a civilization continuously in dialogue with itself—pushing the boundaries of human experience and questioning the essence of beauty and form.

Each sculptural style emerges as a testament to the myriad influences and the inevitable passage of time, offering us a mirror to the ancients’ souls and a bridge to the hearts of civilizations past.

As such, the legacy of ancient Greek sculpture endures, as it continues to resonate with and inspire not just artists but all who seek to understand the depth and breadth of human creativity.

Iconic Works and Artists

Exploring the Greats: Master Sculptors and Their Influential Works

The annals of art history brim with the names of sculptors whose chisels have shaped not just stone but the very course of cultural consciousness. Moving beyond the established greatness of ancient Greek sculpture, one encounters geniuses from Rome to the Renaissance, whose creations still speak volumes to the ardent observer of beauty.

Roman craftsmanship, renowned for its architectural prowess, also gave rise to distinguished sculptors. The mighty empire’s artists, often overshadowed by their Greek forerunners, excelled in portraiture and narratively rich reliefs, capturing emperors and deities alike.

Among these, the unknown creator of the Augustus of Prima Porta stands tall, immortalizing the emperor in a majestic pose that has echoed through centuries.

Transitioning into the Renaissance, an era marked by the revival of classical ideals, we encounter artists whose legacies are inseparable from their masterworks.

Donatello, an early Renaissance figure, reinvigorated freestanding sculpture through his seminal piece, the bronze David, which exudes a nuanced expression of youthful victory and establishes a bold, lifelike approach to the human form.

Contemporaneously, the ineffable mastery of Lorenzo Ghiberti adorns the Florence Baptistery with the Gates of Paradise—a testament to storytelling through relief sculpture that seamlessly blends intricate detail and spatial illusionism, setting a benchmark for narrative art.

The zenith of sculptural innovation is often attributed to Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose Pieta and David embody the pinnacle of Renaissance accomplishment. Both sculptures reveal an uncanny ability to capture human emotions and the complexities of physical perfection.

The Pieta, a rendition of Mary mourning over the lifeless body of Christ, exudes serenity and anguish, while David, standing in defiant anticipation, encapsulates the cultural resurgence of humanist ideals.

Baroque art ushered in Gian Lorenzo Bernini, a virtuoso who breathed life into marble-like no other. His works, including The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa and Apollo and Daphne, exhibit a dynamism that defies the medium’s rigidity, encapsulating moments of intense passion and divine transcendence.

Moving across the channel, one finds Neoclassicism’s restrained elegance in Antonio Canova’s works. His sculptural interpretations of mythological subjects, such as Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, are imbued with serene grace, heralding a return to classical simplicity and highlighting the reflective calm of human emotions.

Each sculptural masterpiece reflects a confluence of historical context, craftsmanship, and the relentless pursuit of aesthetic idealism. Their legacy works surpass mere visual splendor; they are acts of philosophy carved in stone and cast in metal, extending an invitation to ponder the incorruptible beauty of existence.

The works bequeathed by master sculptors remain monuments of artistic excellence and enduring conduits to the sovereign realm of the human spirit, revealing the timeless dialogue between art and life.

Sculpture Techniques and Materials

When the hands of ancient Greek sculptors shaped the very essence of their zeitgeist into the forms of gods, athletes, and ideals, they did so with an intimate knowledge of their materials and a mastery over their techniques that continue to invoke awe to this day.

Artisans of antiquity did not simply carve stone and cast bronze; they breathed life into their works, grounding their creative spirits in the physical world through groundbreaking advancements in sculpture.

Bronze Casting Mastery: The Lost-Wax Technique

The lost-wax casting method was a hallmark of Greek bronze sculpture, a sophisticated process where the original model was sculpted in wax and encased in a clay mold. As the wax was melted away and thus ‘lost,’ molten bronze was poured in, filling the void to create a duplicate in bronze.

Once cooled, the mold was shattered, revealing a lighter hollow bronze figure that allowed for expansive, dynamic forms, best exemplified by the likes of the Riace Warriors. After emerging from its earthen cocoon, the sculpture was subjected to meticulous chasing and polishing. It was often enhanced with inlaid eyes, silver teeth, and copper lips, enlivening the statues with an arresting realism.

Marble Sculpture and the Pointing Machine

Ancient Greek sculptors found a medium to immortalize human perfection in marble, the pinnacle of permanent materials. The earliest form was often local marble, which extended to the highly prized Parian and Pentelic varieties as expertise grew.

The transition from softer stones like limestone to marble signified a transition in skill, the mastery of which was unparalleled in antiquity. Artists would have employed a pointing machine, an adjustable frame with fixed pointers that allowed them to transfer the proportions of a small-scale model to the block of marble at full scale.

Fine details were then sculpted using a variety of chisels, drills, and abrasives, crafting that distinctive blend of idealized form and intricate detail that remains synonymous with ancient Greek art.

Painted Illusions: Polychromy in Stone

Not merely content with the pure hues of bronze and marble, Greek sculptors engaged in polychromy, the painting of statues, to inject vivacity and realism into their creations. While the gleaming white marble sculpture is today’s prevalent image, in antiquity, these sculptures were adorned in vivid colors and pigments derived from natural minerals and applied with binding mediums.

Adds such as red ochre, malachite green, and azurite blue would warm flesh, drape cloth, and highlight hair. Over time, the elements have stripped these statues of their colorful veneers. Still, recent technology reveals the ancient vibrancy, paying testament to the Greeks’ original intention for their sculptures to be as lifelike as possible.

In conclusion, one must perceive ancient Greek sculpture not solely as relics of a bygone civilization but as wild inventions of technique and material that continue to mold our understanding of the human capacity for creation. These masterpieces were brought into existence through lost wax casting, meticulous marble carving, and bold polychromy, cementing their eternal resonance in the pantheon of art history.

Each sculpture, a silent narrator of the narratives and aspirations of those who commissioned them, embodies the tangible connection to the past, the innovative spirit of artists who saw the world not as it was but as it could be, preserved in the art forms they so exquisitely perfected.

Conservation and Display

Preservation of Ancient Greek Sculpture: Enduring Artistry for the Modern Age

Ancient Greek sculptures are testaments to human skill and visionary artistry in antiquity. Over millennia, these sculptures have faced threats from environmental conditions, human interventions, and the passage of time. Today, the conservation and exhibition of these treasures involve a meticulous combination of science, art, and dedication.

The journey from excavation to exhibition for an ancient Greek sculpture is fraught with challenges. Initially, archaeologists handle their discovery carefully, deploying techniques designed to preserve every detail. Stabilization usually begins in situ to fortify the integrity of the material, be it marble, bronze, or terracotta.

Once safely at conservation studios, experts embark on the slow process of cleaning and consolidation. For marble, this often includes gentle washing with distilled water to remove soil and soluble salts, which can crystallize and cause damage. Modern-day intervenors have the advantage of using non-invasive laser technology to clean surfaces meticulously without the abrasion that past methods caused.

Bronze sculptures require a specialized approach to address corrosion and ensure preservation. Historically crafted through the lost wax technique, these bronzes suffer from the inevitable formation of patina.

Today’s conservators employ electrochemical techniques to stabilize and restore the metal’s appearance while respecting the authenticity of the patina, a cherished aspect of their history. Once the conservation treatments are complete, protective wax coatings may be added to shield the sculptures from fingerprints, moisture, and pollutants.

In addition to the structural rehabilitation, research into ancient polychromy upends the misconception of white, unadorned marble. Advances in scientific analysis reveal traces of pigments that lead conservators to understand the vivid colors that once adorned these works.

However, reconstructing original hues occurs selectively in digital simulations or replicas rather than on irreplaceable originals.

Conservation extends beyond the physical to the ethical realm, where the display of Greek sculptures meets scrutinization. Today, museums and cultural institutions aim for a balanced narrative, providing context and avoiding the glorifying acquisition periods marked by colonialism and conflict.

Museums favor empathetic presentations of ancient artifacts, encouraging a cultural sensitivity that fosters a holistic understanding of Greek art’s significance within its native sociopolitical environment.

When sculptures are displayed, climate-controlled environments maintain optimal conditions for their preservation. Specialized lighting highlights the subtle features without causing light damage. Moreover, exhibition design reflects scholarly insights, often reconstructing the sculptures in their historical spatial configuration and giving viewers insights into the original viewing experience.

In a digital age, virtual preservation and exhibition offer a parallel avenue for engagement. Digital scanning and 3D modeling create high-fidelity replicas and interactive experiences that democratize access to these cultural riches, ensuring that geographical limitations do not impede educational opportunities.

In summation, the ongoing preservation and exhibition of ancient Greek sculptures are a testament to our reverence for heritage and a commitment to learning.

Today’s restorers and curators are not merely gatekeepers of history but active participants in an intergenerational dialogue—an exchange that honors the past and informs our continuing discourse on aesthetics, meaning, and the role of art in society.

The challenge of preservation melds with the desire for inspiration, ensuring that these ancient figures stand not lost to time but as vibrant representations of humanity’s ceaseless pursuit of beauty and expression.

The exploration of ancient Greek sculpture reveals a heritage etched in stone and cast in bronze, a testament to the enduring legacy of human expression.

Through the mastery of form, the innovative use of materials, and the daring reach for artistic perfection, ancient Greek sculptors established a canon that still enthralls and inspires.

As these ancient works stand sentinel in museums and collections across the globe, they represent the pinnacle of classical art and challenge us to consider the preservation and interpretation of our shared cultural heritage for future generations to reflect upon and admire.

Anita Louise Art is dedicated to art education, great artists, and inspiring others to find and create their art. We love art that uplifts and inspires. #ArtToMakeYouSmile! #ArtToMakeYouHappy!

If you are interested to see any of my art, you can find out more by clicking here. If you are interested in what inspires me and my paintings, you can discover more by clicking here.

We have a free newsletter and would love you to be part of our community; you can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here. If you have any questions, I would be happy to talk to you at any time. You can reach me, Anita, by clicking here.

Subscribe to our Anita Louise Art YouTube Channel filled with great videos and information by clicking here.

Join us for our podcast “5 Minutes With Art.” Spend just 5 minutes a week with us to discover and learn about great art and artists. You can find out more about our podcast by clicking here.

Related Questions

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Major Works Of Art

Artemisia Gentileschi painted many significant works of art as a full-time artist during her lifetime. She was an extremely gifted artist who gave a unique perspective on the subject matter she was painting. Many of her works of art have hidden messages about the repression of women by men.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Artemisia Gentileschi’s Major Works Of Art.

Is Art A Natural Gift, Or Can Anyone Be Good At Art If They Practice?

Most artists have some natural gift or desire to be an artist. But it is through their education, hard work, practice, and association with other artists that make all the difference. Having a natural gift is the start to becoming an artist, but just having a natural gift will not make you a good artist. Becoming a great artist requires practice, education, and a lot of hard work.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Is Art An Natural Gift, Or Can Anyone Be Good At Art If They Practice?.

Artemisia Gentileschi And Breaking Gender Barriers In Art

In the 17th Century in Italy, women had two career choices: joining a convent and becoming a nun or wife and mother. The laws also dictated that the men in the women’s lives, such as their fathers, husbands, and even sons, would make all the decisions for their lives. Women during this time had very few rights.

By clicking here, you can learn more by reading Artemisia Gentileschi And Breaking Gender Barriers In Art.